Press Page Reinhard Fässler

A Switchblade-like Signaling Machine for Cells

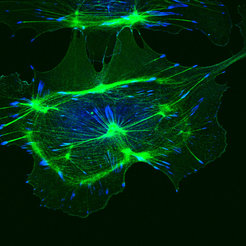

Integrins are anchor proteins that span the plasma membrane and couple the surrounding with the actin cytoskeleton. Integrins play fundamental roles in numerous important processes including cell migration, cell division and blood clotting. Reinhard Fässler and his team study how integrins execute these diverse functions and how malfunctioning integrins affect organogenesis and disease.

Integrins are expressed on all mammalian cells. These transmembrane proteins mediate cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix and thereby connect cells with the surrounding environment. Integrins control a variety of cellular functions including cell survival, shape and polarity, cell proliferation and blood clotting. They also coordinate cell migration, which is important for cancer metastasis, wound healing and inflammation: At the cell front, activated integrins fix the cell to the extracellular matrix. At the cell rear, integrins become inactivated enabling cell detachment from extracellular matrix proteins; this allows rear contraction and the cell to be propelled forward.

Role of adhesion during embryonic and postnatal development

In order to decode the multifaceted functions and effects of integrins, the scientists in Reinhard Fässler’s department inactivate integrin genes in mice. The consequence of this intervention in the germline of mice is that either none or functionally impaired integrins are expressed during development. Depending on the tissue type and the age of the mouse, these modifications can cause a vast variety of phenotypes.

Dysfunctions of integrins give rise to disease

In a severe hereditary disease, called Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency (LAD) type III, immune cells can no longer extravasate from the blood circulation into tissues and platelets cannot clot, thus leading to severe bleeding. Fässler’s team was able to show that patients who suffer from this disease lack a protein necessary to activate integrins on white blood cells and platelets. Given that defective integrins almost always lead to diseases, the results from Fässler’s team may help to develop new drugs in the future.